By Hannah Esqueda

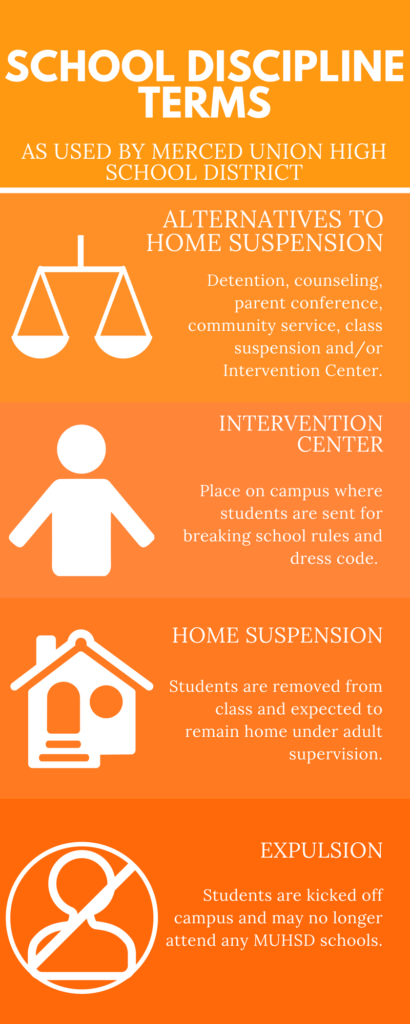

Image via Dignity in Schools

Editor’s Note: As the 8th Annual National Week of Action Against School Pushout is underway, our reporter Hannah Esqueda took a closer look at disciplinary policies imposed by the Merced Union High School District. While data shows suspensions have been reduced through restorative justice practices, student experiences suggest there is still a lot of work to be done in Merced schools.

MERCED, Calif. — Discipline policies at California public schools have evolved over the years to reflect social norms.

From corporal punishment–legally allowed in schools until 1986–to zero-tolerance policies with immediate suspension and expulsion for students, a variety of tactics have been used to regulate student behavior and performance.

It wasn’t until the last decade or so that public schools began experimenting with more progressive alternatives, said Lori Mollart, director of child welfare, attendance and safety at Merced Union High School District.

Over the last decade, school districts throughout the state have begun to reevaluate “black-and-white policies that would discipline students automatically regardless of individual circumstances,” she said.

Much of this coincided with the passing of Assembly Bill 1729, which allowed superintendents and principals more discretion to provide alternatives to suspension and expulsion for students, said Mike Richter, associate principal at Golden Valley High School (GVHS) in Merced.

Teachers and staff are now encouraged to look at a student’s complete behavioral pattern before determining an appropriate course of action.

That’s important, as suspension policies have recently been connected with the achievement gap among many of California’s minority student populations.

A report released this week by the The Civil Rights Project at the University of California, Los Angeles found that California students lost more than 840,000 days of school instruction during the 2014-15 academic year as a direct result of home suspension policies.

According to the study, time spent out of the classroom means students have a tougher time catching up to their peers, ultimately leading to lower graduation rates.

And while local school districts heavily monitor student attendance–even going so far as to arrest parents of students with too many unexcused absences–there is often less discussion of the ways discipline policies can cause similar harm.

Home suspension and its alternatives

Over the last decade, Merced Union High School District (MUHSD) has managed to significantly reduce the number of home suspension days seen by students– dropping from a high of 6,409 days suspended students spent out of school in the 2008-09 academic year, to 1,265 in 2016-17.

Such a steep decline is due in part to an overhaul in the district’s approach to discipline. Since 2012, many MUHSD campuses began adopting restorative justice practices and converting in-school suspension programs to the more progressively themed “Intervention Center.”

Abraham Olivares, associate principal at Merced High School and one of the creators of Golden Valley’s Intervention Center (IC), said campuses measure the success of IC’s by decrease in home suspension.

Students are mainly sent to the IC for minor-level discipline issues like talking back to instructors, not following direction or being off-task, Richter said.

“Really, students are given every opportunity to stay in the class,” he said. “It’s up to the teacher’s discretion to send them to [the IC].”

Theoretically, administrators say, IC’s provide a supportive environment where students can identify and discuss the specific behavior that saw them dismissed from class in the first place. This is typically done through a mediation form (often referred to as a “greensheet” by students because of the color) where teachers outline the problem for the student to respond to and identify alternative behaviors.

“Students reflect on what they’ve done and how they can improve,” Richter said. “That [greensheet] is their ticket in the door [to the IC].”

Current and former students at GVHS say that’s how the system works in theory, however the everyday practice can sometimes differ.

“In the IC, they don’t always even check for greensheets. I’ve been sent away without one before,” said Aaliyah Jensen, a 16-year-old former GVHS student. “You just sign in, and sometimes no one’s even watching that.”

While not two IC’s in the district are alike, Mollart said each one is designed to be taught by a “highly-qualified teacher.”

“Which just means they have a teaching credential,” she continued.

Olivares and Richter confirmed that the current instructor in charge of Golden Valley’s IC is credentialed, but said that rule is fairly new in practice.

“It’s been a process getting the center up and running and we’ve learned as we go,” Olivares said. “In the beginning, we had hourly employees in there because it’s a tough [assignment].”

Once inside the IC, students are meant to reflect on the actions which landed them there, said Megan Cope, associate principal at Golden Valley.

“They’re in there sitting and reflecting on their behavior,” she said.

Reflection includes filling out the greensheet paperwork, but students interviewed say they would more often sit around in the IC without working on anything. Computers and electronics are not allowed in the IC unless special permission is given for an assignment.

“It’s pretty boring in there. You just sit and do nothing,” Jensen said. “Sometimes you can leave the room if no one’s paying attention.”

In those cases, Jensen said she’d walk around campus until either caught or the period ended. Other times she recalls using a bathroom pass to hide away in the restroom for the remainder of the period.

Students sent to the IC by a particular teacher need only remain there for that period, Cope said. Dress code violations are also sent to the IC to check-in, and students can then either call a parent to bring in a change of clothes or borrow extra clothes from the IC.

“They’re loaner clothes from P.E.,” she said.

“No one wants to wear those clothes though,” said Layla Ornelas, a 16-year-old junior at GVHS.

“I went in once and they tried to give me this baggy shirt that was like five sizes too big. There was a hole in the armpit and the neckline was so big it would end up being more revealing than the top I was already wearing,” she continued.

Ornelas said that she, like most other students in that situation, refused to wear the IC clothes.

“My outfit was hella cute so I wasn’t going to change into the stinky clothes anyway,” Jensen added.

Students who refuse to change clothes or call their parents to bring new ones spend the rest of the day sitting in the IC, Olivares said.

“It’s pretty boring in there. You just sit and do nothing,” Jensen said. “Sometimes you can leave the room if no one’s paying attention.”

Vulnerable to School Pushout

While administrators say the dress code is enforced equally on young men and women, Ornelas and Jensen had different takeaways, with each saying the code unfairly targets young women, or those who don’t conform to traditional gender norms. The latter of which is of serious concern as research shows LGBTQ-plus youth of color are particularly vulnerable to school-pushout and the school-to-prison pipeline.

Administrators at MUHSD said the school does not currently track LGBT students for discipline data, but does pull some information from the annual California Healthy Kids Survey to help keep tabs on bullying.

“Students have the option about how public their identities are and we are sensitive to that,” said Debbie Glass, director of equity and accountability with MUHSD.

“I imagine it’s something we’ll begin looking into in the near future though,” she continued.

In the meantime, district and campus officials are likely to continue tracking discipline data for most other students populations. Such information is a requirement of the recently created school dashboard which monitors school progress towards closing achievement gaps and improving graduation rates.

Golden Valley’s Spring 2017 profile shows the school having suspension rates in the single-digits for all measurable student categories and populations, a feat administrators point to as a key sign of success for the IC.

“It’s an ongoing process and we’re learning all the time from students,” said Richter. “At it’s core the IC program is about the teacher-student relationship–repairing that relationship when needed in order to keep students in the class.”

For more about the Week of Action Against School Pushout, you can visit the Dignity in Schools website here.

Translate

Translate